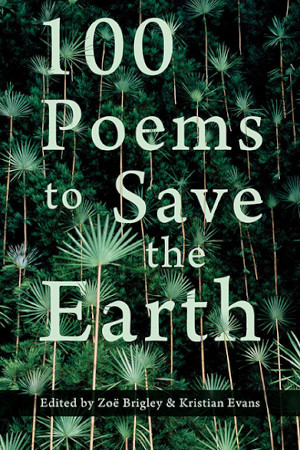

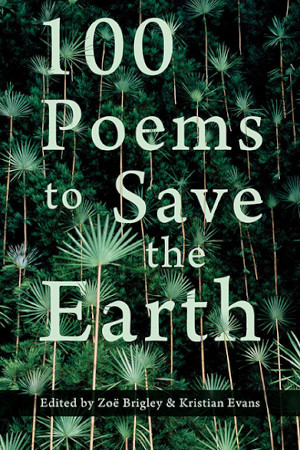

How could a single poem, or 1000, hope to save our world? That’s the question laid out by Seren in their latest anthology, 100 Poems to Save the Earth. In 127 pages they answer time and again – through revealing the ecstatic beauty of nature, and its perilous fragility, as expressed here by poets ranging from Simon Armitage to Sheenagh Pugh to Alice Oswald.

How could a single poem, or 1000, hope to save our world? That’s the question laid out by Seren in their latest anthology, 100 Poems to Save the Earth. In 127 pages they answer time and again – through revealing the ecstatic beauty of nature, and its perilous fragility, as expressed here by poets ranging from Simon Armitage to Sheenagh Pugh to Alice Oswald.

The anthology’s editors, Zoe Brigley and Kristian Evans, state in the Introduction that “we live in a time of unprecedented crisis”, but that poetry “calls us to stay awake, to find the words to describe how it feels, to sing to what hurts, to reach out, to attend more closely and with more care, (…) to see all things as our kin.”

In Chorus, David Morley reminds us how “The swallow unmakes the Spring and names the Summer” while “The bullfinches feather-fight the birdbath into a bloodbath”. It’s a vivid reminder both of the majesty of nature, and the characteristics we’re prone to share.

Some of the poems ache with such exquisiteness that I felt a lump in my throat as I read. Carrie Etter’s Karner Blue is one such work, with its echoing refrain of “Because” drawing you in: “Because its wingspan is an inch./ Because it requires blue lupine./ Because to become blue it has to ingest the leaves of a blue plant.” And once we’ve marvel at the wonders that comprise this butterfly, the damning line is served: “Because it has declined ninety per cent in fifteen years.”

Yearning lines abound throughout, urging us into wild spaces: “I go and lie down where the wood drake/ rests in his beauty on the water” (The Peace of Wild Things, Wendell Berry); “Stride out with your boots on, or, better still/ barefoot, and be inside the wind a while” (Water of AE, Em Strang).

Meanwhile, Isabel Galleymore’s Limpet & Drill-Tongued Whelk devotes 14 lines to seaside molluscs, describing a limpet as: “moon textured, the shape of light/ pointing through frosted glass.”

Elsewhere there are conversations with and between trees, and “redwoods veined with centuries of light” (Earth, John Burnside), while Kei Miller brings us the world’s palette in To Know Green from Green. In Sean Hewitt’s Meadow, loss of a loved one tangles in with “the beehive’s sultry/ murmur” as the poet watches “each floret and petal/ inscribe life in its colour.”

Nature in this context offers both consolation and affirmation.

The anthology contains countless lines of awe regarding our wild neighbours, from fungus to octopus, woven in with notes of foreboding. One of the most chilling for me vaults from Sina Queyras’ From ‘Endless Inter-states’: 1, in which the narrator offers “coffee, hot while there is still/ coffee this far north, while there is still news/ to wake up to, and seasons”.

There’s humour too, as in Rhian Edwards’ The Gulls are Mugging and Samuel Tongue’s Fish Counter, which offers “Wise lumps of raw tuna”, “Fish fingers mashed from fragments of once-fish”, and “Hake three-ways”, before delivering the warning: “Choose before the ice melts.”

Near the end, in Dom Bury’s Threshold, we uncover the urgency beneath these poems – these declarations of love, of alarm, of sadness amid beauty, as the poet shares the realisation “That we have to be taken to the edge of death/ to choose, as one, how we live.”

A thought-provoking, at times disconcerting, occasionally heartbreaking, but more often veneration-inspiring hoard of nature-observations, this anthology speaks the message we all need to hear: we must do more than just notice nature to save it and ourselves, but noticing is a good first step.

100 Poems to Save the Earth, edited by Zoe Brigley and Kristian Evans, is published by Seven Books and available to buy here.

This book was given to me in exchange for a fair review.

What are you reading? I’d love to know. I’m always happy to receive reviews of books, art, theatre and film. To submit or suggest a book review, please send an email to judydarley (at) iCloud.com.