George and Martha invite Nick and Honey to join them for a nightcap. It’s way too late in the evening, but what do they have to lose?

So reads the description on the Tobacco Factory Theatres’ website, and the answer is really quite a lot. Dignity, trust and self-respect are just a few of the traits that will be ripped to shreds by the end of the three act, three-hour and 15-minute performance.

Martha (Pooky Quesnel) and George (Mark Meadows) are already deeply embedded in the academic community that Nick (Joseph Tweedale) and Honey (Francesca Henry) have just joined, so perhaps it’s natural that the younger couple accept an invitation for a post-party party at Martha and George’s. But even the hosts aren’t prepared for the toxic darkness of the games that unfold between the four players.

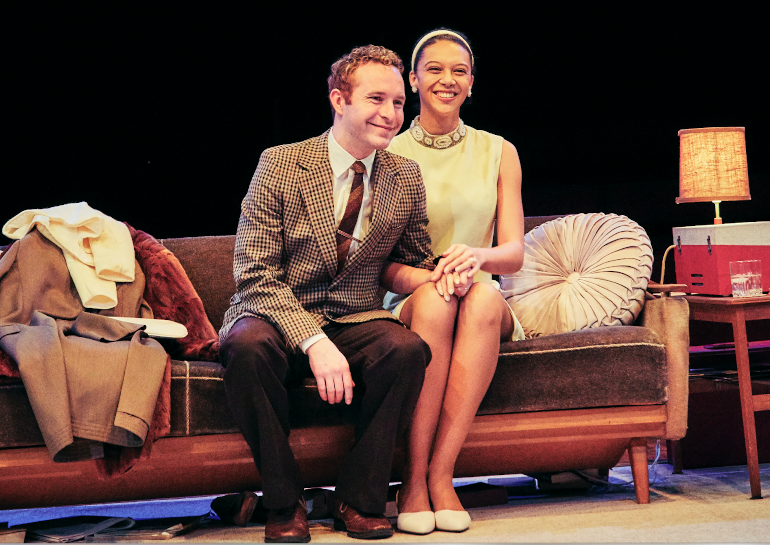

Joseph Tweedale and Honey Francesca Henry as Nick and Honey in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf at Tobacco Factory Theatres, Bristol. Photo by Mark Dawson

The drama is almost entirely semantic (despite some exuberantly comic dancing from Henry). In Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, language is weaponised, and aimed to cause maximum damage. Director David Mercatali says “When I first read it, I couldn’t believe words could be so exciting.” His four-strong (extremely strong) cast make the most of Edward Albee’s scorching lines, veering from joyful to tearful and vindictive to protective on the head of a pin. At the heart of it is a couple disappointed by circumstance, and displacing that onto each other despite a deep burning love. Without the affection and evident flickers of adoration, the cruelty might be impossible to bear.

Pooky Quesnel as Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf at Tobacco Factory Theatres, Bristol. Photo by Mark Dawson

Quesnel eases us in with a double-feat of performing Martha doing an impression of Bette Davis, with a touch of Elizabeth Taylor thrown in. George already has his slippers on before she announces they’re expecting guests, delivering her first kick to George as he berates her for “springing things on me all the time.”

Meadows delivers George’s commentary with razor-sharp humour.

“In my mind you are bedded in cement up to the neck,” says George to Martha in an acerbic moment. “No, up to the nose, it’s quieter.”

The laughter, anecdotes and snarky remarks grow increasingly frantic as the booze flows and each individual makes admissions that they’ll most likely regret. A gun presents a joke and flowers become missiles while a broken bottle crushes to dust under their feet.

The Tobacco Factory’s in-the-round space presents the ideal arena for the challenges, with Anisha Fields’ minimal set providing only the essentials – two chairs, a long low backed (thankfully – for those sitting behind it) sofa with books strewn beneath it, a side table with a record player, and a well-stocked bar. It paints the era without fuss, and keeps our focus on the couples.

Quesnel is startling and unnerving, veering from welcoming hostess to seductress to weeping child desperate for love. Meadows is equally adept, revealing George’s underlying rage in small parcels between entreaties and insults. Over the course of the play he refers to Martha as his “yumyum”, and a “cyclops” without missing a beat. And when Honey coyly asks to use the bathroom, George says to Martha: “Show her where we keep the euphemism?”

Tweedale’s Nick holds his own against George, defending both his own wife and Martha against the barbs that come their way, even as the alcohol reduces him to a jocular jock, leaning into the toxic tomfoolery. Henry’s Honey is keen to like and be liked by all, slipping in observations that strip away the veneer momentarily. Her comic timing lifts some bleaker moments into laughter, keeping us on the right side of this emotional juggernaut of a play.

It is long, and could perhaps benefit from having a few lines shaved off here and there, especially in act two. But it’s hugely enjoyable too. Even as you squirm in your seat for those on stage, feeling your own adrenalin heighten, you can’t help being aware of the glory of seeing sharp minds battle it out and wonder who if anyone will make it out alive.

A searing indictment of thwarted ambition, with deep sadness and enduring love at its heart.

Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is on at Tobacco Factory Theatres, Bristol, until 21st March 2020.

Images: Mark Dawson Photography.

Seen or read anything interesting recently? I’d love to know. I’m always happy to receive reviews of books, art, theatre and film. To submit or suggest a review, please send an email to judydarley(at)iCloud.com. Likewise, if you’ve published or produced something you’d like me to review, get in touch.

Gathering together 137 stellar micro fictions,

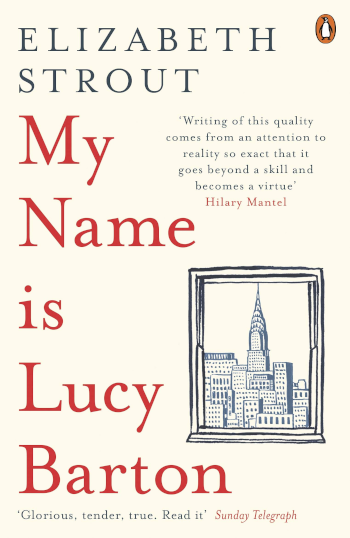

Gathering together 137 stellar micro fictions,  I have a stubborn streak that makes me shy from the books that hit mainstream esteem. Part of me wants to seek out the underdogs that will really benefit from the boost of a review. However, My Name Is Lucy Barton is the story of a woman whose childhood placed her squarely in the camp of underdog, with a level of poverty that Elizabeth Strout paints with visceral skill, rendering it utterly relatable without oiling the hinges with sentimentality.

I have a stubborn streak that makes me shy from the books that hit mainstream esteem. Part of me wants to seek out the underdogs that will really benefit from the boost of a review. However, My Name Is Lucy Barton is the story of a woman whose childhood placed her squarely in the camp of underdog, with a level of poverty that Elizabeth Strout paints with visceral skill, rendering it utterly relatable without oiling the hinges with sentimentality. I’ve been reading and rereading books from numerous independent presses recently. Here’s my pick of the titles I believe warrant a place on your festive wishlist.

I’ve been reading and rereading books from numerous independent presses recently. Here’s my pick of the titles I believe warrant a place on your festive wishlist. Nia by Robert Minhinnick

Nia by Robert Minhinnick

The False River by Nick Holdstock

The False River by Nick Holdstock She Was A Hairy Bear, She Was A Scary Bear by Louisa Bermingham

She Was A Hairy Bear, She Was A Scary Bear by Louisa Bermingham the everrumble by Michelle Elvy

the everrumble by Michelle Elvy Unexpected gems abound in

Unexpected gems abound in  I recently experienced the joy of arriving home to a package full of poetry collections from the inestimable Seren Books. It got me wondering what a collective noun for poetry collections should be. A library seems too literal, so I began thinking about what poetry offers – how it provides the space to pause and reflect before carrying on with the busy act of living. So, a poetry collection is a coppice, in the forest of everyday life.

I recently experienced the joy of arriving home to a package full of poetry collections from the inestimable Seren Books. It got me wondering what a collective noun for poetry collections should be. A library seems too literal, so I began thinking about what poetry offers – how it provides the space to pause and reflect before carrying on with the busy act of living. So, a poetry collection is a coppice, in the forest of everyday life.

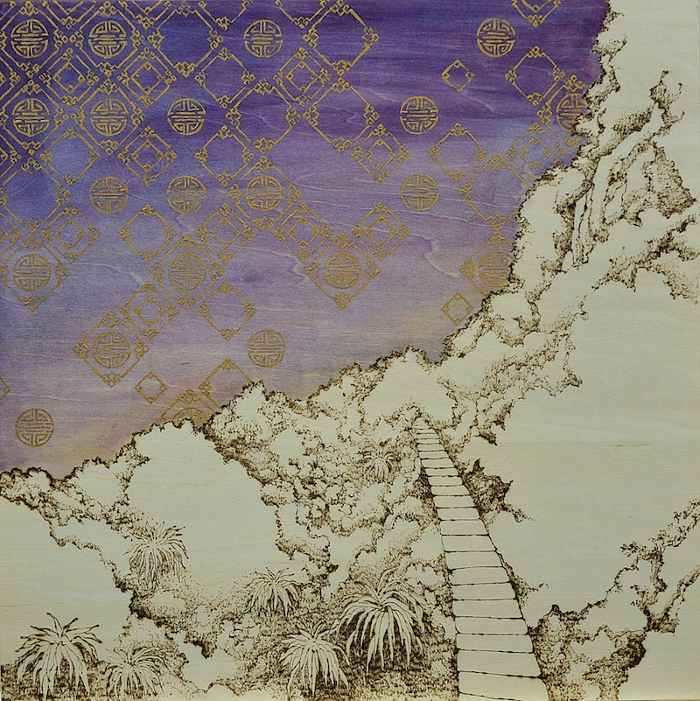

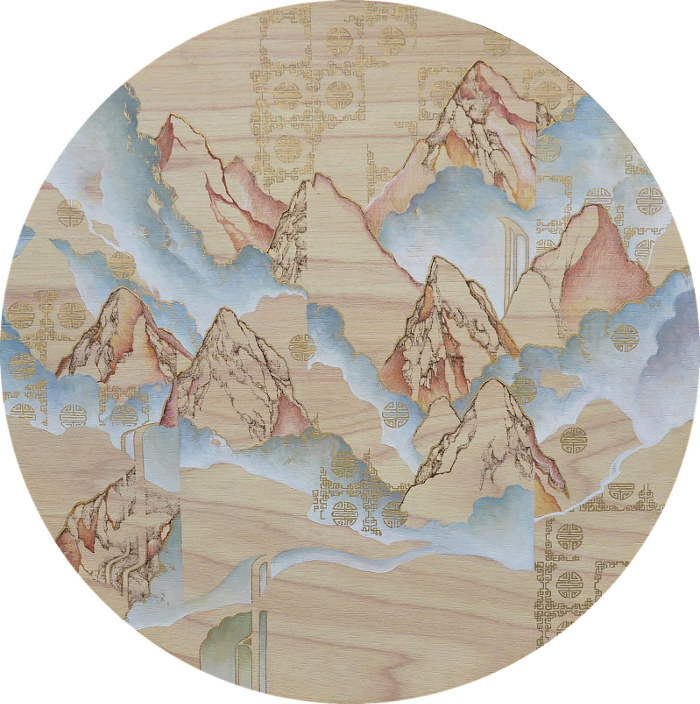

Sometimes an artist’s power lies in their prowess with certain techniques and materials. With accomplished

Sometimes an artist’s power lies in their prowess with certain techniques and materials. With accomplished

I became aware of Olafur Eliasson thanks to ‘

I became aware of Olafur Eliasson thanks to ‘

The Royal West of England Academy (RWA) is currently holding an exhibition that examines the beauty and peril of fire.

The Royal West of England Academy (RWA) is currently holding an exhibition that examines the beauty and peril of fire.