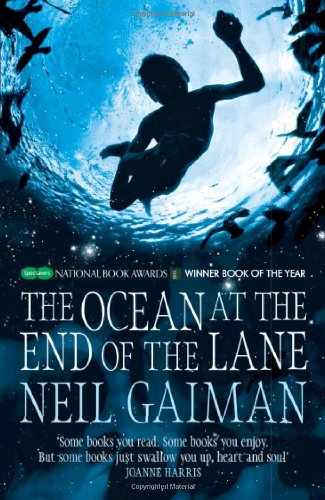

They say you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, and while it isn’t why I decided to read Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane, there’s no denying the shiver of pleasure I felt whenever I glimpsed it. Featuring the silhouette of a skinny boy swimming in a fathomless ocean, it led me to expect a protagonist with the bravado and wildness of JM Barrie’s Peter Pan.

They say you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, and while it isn’t why I decided to read Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane, there’s no denying the shiver of pleasure I felt whenever I glimpsed it. Featuring the silhouette of a skinny boy swimming in a fathomless ocean, it led me to expect a protagonist with the bravado and wildness of JM Barrie’s Peter Pan.

Far from it. Gaiman’s hero is an ordinary man remembering being an ordinary boy, and that, without doubt, is part of the beauty of this tale. When a lodger his parents take in dies, the boy, who remains nameless throughout, meets the three Hempstock women for the first time – Old Mrs Hempstock, Ginnie and Lettie, marvellous, resourceful Lettie who seems to be eleven years old, but answers only with a smile when asked “How long have you been eleven for?”

Gaiman weaves magic into the story with deft matter-of-factness. The boy takes it in his stride, with a child’s acceptance that the world is, of course, filled with things he doesn’t understand. He reads voraciously, mainly his mother’s old novels crammed with children foiling spies and criminals, and relishes simple details such as sleeping with the windows open so he can listen to the wind and pretend he is at sea.

When the lodger commits suicide something is stirred into wakefulness and needs to be bound to its place. Lettie takes the task on, and brings the boy with her into a place with a sky “the dull orange of a warning light.” It’s a journey which leads a mass of horrors that Gaiman refers to subtly enough to require us to do some of the imagining, the neatest way possible to ensure we take on the boy’s terror as our own.

A bold thread to the tale reminds us that being scared is something that comes with age, with knowledge, so that only the very young are truly unafraid. “I was no longer a small boy,” says our protagonist, ruefully. “I was seven. I had been fearless, but now I was such a frightened child.”

There’s a skill to perfectly balancing dread, suspense and beauty in a fairytale. Gaiman manages it with enviable ease, often offering comfort in the form of food from the Hempstocks – paper-thin pancakes blobbed with plum jam, honeycomb “with an aftertaste of wild flowers”, drizzled with cream from a jug. It’s at once utterly, earthily bucolic, and curiously reminiscent of the meals eaten by fairies in the stories I read as a child.

The horror comes in the form of the unnamed creature who hangs in the sky like “some kind of tent,” with a ripped place “where the face should have been.” Cleverly though, that’s far from the worst of it, as Gaiman gives her human form, then lets her get the boy’s father to do terrible things.

“You made my daddy hurt me,” the boy says, and she laughs, then declares that she never made any of them “made any of them do anything.”

It’s a chilling revelation, this idea that however much she may have encouraged, or even cajoled, the deeds committed came from some dark place deep inside the boy’s father, not from the monster’s will.

And then there’s the ocean, at the end of the lane, that resembles a duck pond yet contains all the depths of the universe, and, it seems, all its possibilities too.

A beautiful book – grotesque and magical – that every adult should read, if only to remember the brave, frightened children they once were.

The Ocean at the End of the Lane by Neil Gaiman is published by Headline and is available to buy from Amazon.

To submit or suggest a book review, please send an email to Judy(at)socketcreative.com.

The beautiful book is one of the most unusual tales I’ve read. Told entirely from the point of view of a single bee, Flora 717, it encompasses a whole life and society, from the confines of a hive to the surrounding orchard and beyond.

The beautiful book is one of the most unusual tales I’ve read. Told entirely from the point of view of a single bee, Flora 717, it encompasses a whole life and society, from the confines of a hive to the surrounding orchard and beyond.

There is a delicious sense of solidity to the poetry in Angela Cleland’s

There is a delicious sense of solidity to the poetry in Angela Cleland’s