As authors we’re often asked to define our writing genre, but is this always the right option? Today’s guest post author, Kate Dunn, thinks not.

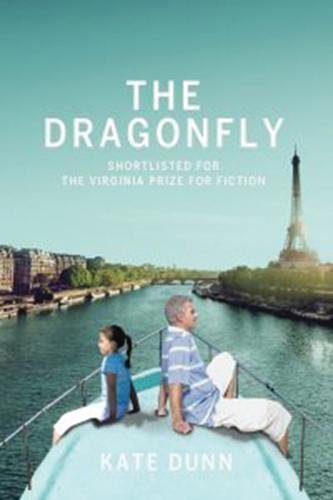

An article in the Kirkus Review about my new novel The Dragonfly mentioned that it is difficult to categorise, something that I was rather pleased about as I was keen not to bend the integrity of the story to fit into a particular niche. It is an unusual tale. Its two central character are a middle-aged man, Colin, and his nine-year-old French granddaughter Delphine, who are thrown together after the death of Delphine’s mother Charlotte.

To divert her from her sorrows, Colin decides to take her on an extended trip on his little day boat, the Dragonfly. Having these two protagonists at the heart of the novel already creates certain tensions – they come from different generations, genders and countries; they don’t even share a common language, so there is plenty of scope for conflict here and therefore the potential for drama.

Locate the emotional truth

I set myself more challenges than perhaps I meant to with these two. Neither Colin nor Delphine come from worlds which particularly chime with my own and I find it very difficult to account for their origins and evolution: they made themselves known to me.

What I’m trying to do in creating characters is to locate the emotional truth in each of them. That seems to dictate how they speak, how they think, how they behave and I guess there is a certain universality in the emotions all of us feel – the author’s job is to make these individual and particular to each of her characters. I’m slightly superstitious about analysing whatever it is that happens during this process, in case it stops working!

The book has two different locations: firstly, the achingly beautiful canals which wind through the Burgundy countryside in France. My husband and I are lucky enough to have a little river boat which we keep on the French waterways.

We have had rather more adventures then I would like: it turns out that as a sailor I have a very low threshold of panic and an over-active imagination – not good for boating but quite productive in terms of writing fiction, and I have certainly drawn upon some of our scrapes when plotting The Dragonfly.

Colin’s boat is based on one we saw moored in a marina – it was absolutely tiny and a middle-aged man and his granddaughter had been sailing on it together for thirty-six days. That got me thinking…

Draw from unconventional experiences

The sub plot of the story takes place within the four walls of a prison cell in Paris where Colin’s son Michael is awaiting trial for the murder of Delphine’s mother, living in close proximity to his villainous cellmate Laroche while attempting to come to terms with recent tragic events.

One of my first jobs was working as a solicitor’s clerk and occasionally I had to visit prisoners on remand in Brixton prison – seeing the conditions back then had a huge impact on me and certainly informed the writing of these scenes.

My years spent in a particularly grim English boarding school helped as well: the place was spartan and institutional and the iron bedsteads (complete with horsehair mattresses) had Kent Summer Prison stencilled on them. It was a brutalising regime and left an indelible impression on me, which I think also may have influenced my portrayal of the dynamics at play in my Paris prison.

I wanted Colin and Delphine to begin their adventure together from opposite poles in order to create enough space for them to reach out to one another. To increase their stress levels, I decided to place all of my characters in situations where space is the one thing that isn’t available to them: Colin and Delphine are on a small boat, and Michael and Laroche are confined to a cell.

I wanted Colin and Delphine to begin their adventure together from opposite poles in order to create enough space for them to reach out to one another. To increase their stress levels, I decided to place all of my characters in situations where space is the one thing that isn’t available to them: Colin and Delphine are on a small boat, and Michael and Laroche are confined to a cell.

My hope was that in setting up these polarities within the story and putting my characters in a pressure-cooker situation, I would maximise the opportunities for narrative tension: there is plenty of warp and weft in the novel. There are all kinds of contrasts at play that might not have been available to me if I had confined myself strictly to one genre. A thread of domestic violence runs through the book, posing some tricky questions: can a victim ever be complicit in what happens to them? Does the fact that somebody commits a violent act preclude them from being otherwise decent and well meaning?

These are issues I wanted to explore, without necessarily coming up with answers – I’ve left that to the reader to decide. Although the central theme is serious, there is lots of humour in The Dragonfly, which provides another source of structural tension. The fact that the story straddles different genres and can be read as a mystery or thriller, a family drama, a love story, an adventure full of mishap and misjudgement or even a road trip, is an expression of all the contrasts and contradictions that define it.

Kate Dunn comes from a long line of writers and actors: her great-great-grandfather Hugh Williams was a Welsh chartist who published revolutionary poetry, her grandfather, another Hugh Williams, was a celebrated film star and playwright, and she is the niece of the poet Hugo Williams and the actor Simon Williams.

Kate has had six books published, including novels Rebecca’s Children and The Line Between Us, and non-fiction books Always and Always – the Wartime Letters of Hugh and Margaret Williams and Exit Through the Fireplace. Her novel The Dragonfly was shortlisted for The Virginia Prize for Fiction.

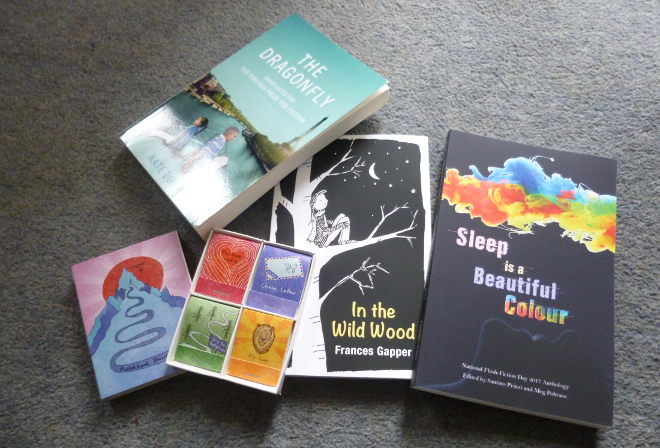

All images in this guest post have been supplied by Kate Dunn.

Read my review of The Dragonfly by Kate Dunn.

Got some writing insights to share? I’m always happy to receive feature pitches on writing genres and writing tools. Send an email to Judy(at)socketcreative.com.