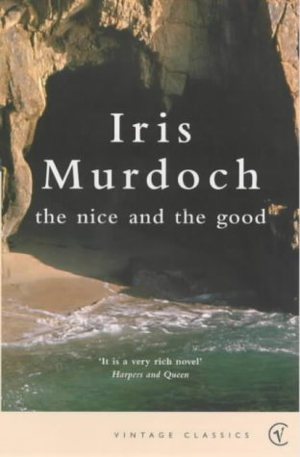

There is a scene in The Nice And The Good by Iris Murdoch that encompasses everything you need to know about suspense writing.

There is a scene in The Nice And The Good by Iris Murdoch that encompasses everything you need to know about suspense writing.

Plumped 295 pages towards the end of the 1969 edition of this rather meandering novel, it involves Gunnar’s cave, “its sole entrance only above water for a short time at low tide.” Murdoch drops this line in far earlier, building on the cave’s status in “the mythology of the children.”

For 15-year-old Pierce in particular, this sea cave is a place of fascination and dread. He fears it more than the other children do, and, equally, wonders about the possibilities of this hidden space, and marvels over the chance there could be a secret safe spot in there, or whether one would inevitably be drowned.

Towards the end of the novel, his heart has been broken, he’s cross with the world, and his behaviour is becoming increasingly erratic. The cave, seems to be the answer to this – the opportunity to face the threat head on, while allowing it to prise from him the choice of life over death. Once inside, with the entrance sealed by the tide, he will be at its mercy, and that, in his current state of mind, is oddly appealing.

But even this disastrous plan doesn’t go quite to plan. No sooner is he swallowed up by the darkness than he hears splashing nearby and discovers that Mingo, the family dog, has followed him in. Then John Ducane, a friend of his mother’s, swims in to see if he can find the boy. Now three lives are at peril in a dense, cold, alien blackness of the cave, and the reader (in my case, at least), is transfixed.